LIVING WITH THE GHOST OF MASON BUT NOT MONROE

Or am I imagining it?

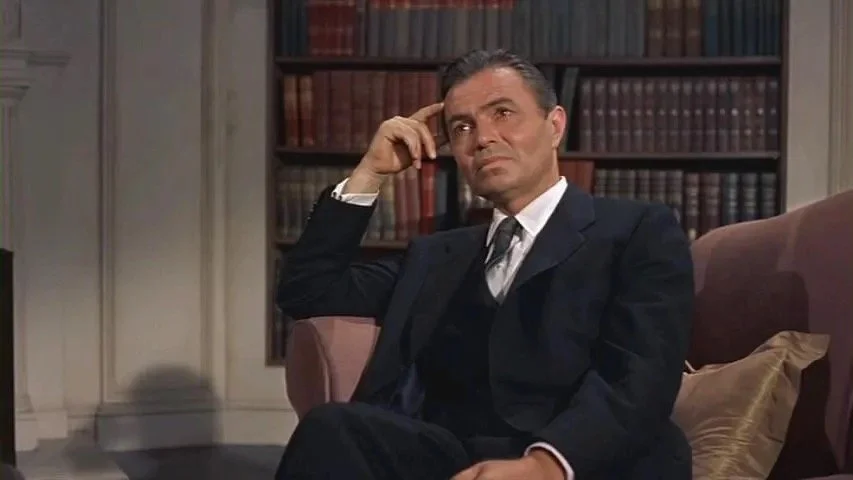

James Mason in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest. Cinematography Robert Burks

Among the movies I watch each and every year, North by Northwest from 1959 never fails to delight me with its wit and elegance. Maybe it’s because I’m a Londoner — as the song used to go, I guess still does (if anyone sings it now) — maybe it’s because I’m Londoner, or was, that I love the cinema of Londoner Alfred Hitchcock. Vertigo, is my favorite film, Notorious, Marnie, Shadow of a Doubt, some of many others by the maestro that I revere…

Cary Grant and Eva Marie Saint are, of course, key elements in NBNW’s charm and glamour — but there is someone else there who renders this such a great movie, someone who chills the arteries of the picture’s otherwise agreeable romance…

James Mason is one of three fellow Englishmen at the heart of this film, Grant and Hitchcock the other two comprising the triptych.

Mason is momentous in Ophuls’ 1949 Reckless Moment too, and in that master’s Caught, released the same year. And as Humbert Humbert in Kubrick’s 1969 Lolita, bringing to life Nabokov’s reprehensible protagonist with a panache only the suave Yorkshireman could vest in the role.

In something over 120 films, over half a century of cinema, Mason’s enigmatic persona — ever a compelling mystery, whatever the nature of the character he brought to the screen — captivated, and continues to captivate viewers fortunate enough to witness his icy but all too flawed human magnetism.

An unlikely connection to James Mason prompted me to conceive of this article, for without doubt, he would have had occasion to walk into the very room in which I’m writing these words. You see, he once owned this apartment, this building and its few units. As its landlord, he would surely have studied the moldings I study, looked up at the high tray ceiling, surveyed the long living and dining area, and the arches dividing it. He would have peered out from the same high window at the plain I observe today, a prospect punctuated by palms and criss-crossed by neighborhood streets — less in his time maybe, more now—as it advances to hills hazy beyond.

But when was this? Was it during the months Dorothy Dandridge lived in the apartment that I see, behind a central leafy enclave, in the building down the hill below? Dandridge, whose nomination for Best Actress at the Academy Awards was the first for an African American. Singer, actor, boundary-breaker, she died, I think, in that apartment, tragically at the age of 42.

Was James Mason here when someone else graced that apartment’s Hollywood feng shui? Someone before Dandridge? Someone called Marilyn Monroe. Did he visit her there, Monroe? Or visit Dandridge after? Did he ever go into that apartment as I have? Or am I conjuring meetings and greetings that never happened? Or perhaps they did, given Hollywood’s social firmament — not there but elsewhere, away from these hallowed residences?

There’s other fanciful, previously celeb-inhabited architecture in this neighborhood. (This once James Mason-owned property being noticeably fanciful itself.) Director Joseph Von Sternberg (originally Jonas Sternberg, without the Von) lived down the road in one such old Hollywood edifice with his wife and Marlene Dietrich. Ménage a trois — or perhaps drei — on Fountain. F.Scott Fitzgerald lived and died just a few streets away, adjacent to a contemporary writer friend who keeps radiant the flame of the LA artist-intellectual.

The Garden of Allah, playground for the stars, stood up on Sunset — before its paradise was paved to put up a parking lot. (Maybe something came in between but I like the irony — and now the parking lot itself has been ripped up, leaving nothing but a legal mess plus the potential for a fresh chorus.)

But back to the room in which I sit. These apartments came into being in the silent era, as I understand, for actors employed by the studios. Who else might have sat where I’m sitting, I wonder? And how many ghosts might populate some multiple occupancy of shades around me? Or did James Mason, with his steely authority, evict the lot of them? Am I then left with the revenant of the great man calling in from time to time to inspect a property once his?

Why shouldn’t a soul as impenetrable as his have left a trace perhaps tantalizingly faint but ever present nevertheless? Not a ghost that comes and goes perhaps, or the wraith that drifts from one room to another but a breath to suffuse the light from the south incandescent through the panes of that high window—wintry in its SoCal warmth.

Then again, why should James Mason, in particular, leave behind such a penumbra? Why not Monroe, even if she took residence across the way. Surviving as an icon, though, she hardly requires spectral continuation. Mason not so. A star, a leading man or a leading villain rather than an idol — yet if anyone could cheat the gods to maintain a presence among the living, he maybe could.

Or is it simply that those eyes of his I see on the screen can never be entirely shaken off? They could be here now. Seeing into me as I write. As they saw into Cary Grant’s Roger Thornhill or Eva Marie Saint’s Eve Kendall in Hitchcock’s North by Northwest.

Mason could do that, spear the heart of any he observed. Whether he was Hitchcock’s Phillip Vandamm or Ophuls’ Martin Donnelly or Dr. Larry Quinada, he could see into the very core of the characters he confronted. It was as if he could see elsewhere too, out from the screen before us and into our own souls as though to render us ourselves the uncertain, vulnerable characters foolhardy enough to inhabit his fictive universes.

For me, it is looks that linger rather than lines of dialogue — and the sound of speech rather than its words. It’s the looks that have the charge, the connection, the ineffable power. It’s the vocal timbre that resonates.

James Mason, with his pellucid, piercing gaze, with the music of his rich and burnished tenor, haunts my recall, and, I suspect with increasing conviction, this apartment in which I live, for as long as it endures — and, who can say? — haunts whatever it might be that comes to stand in its place…

Peter Markham

January 2026