Academic exercise or invaluable filmmaking resource?

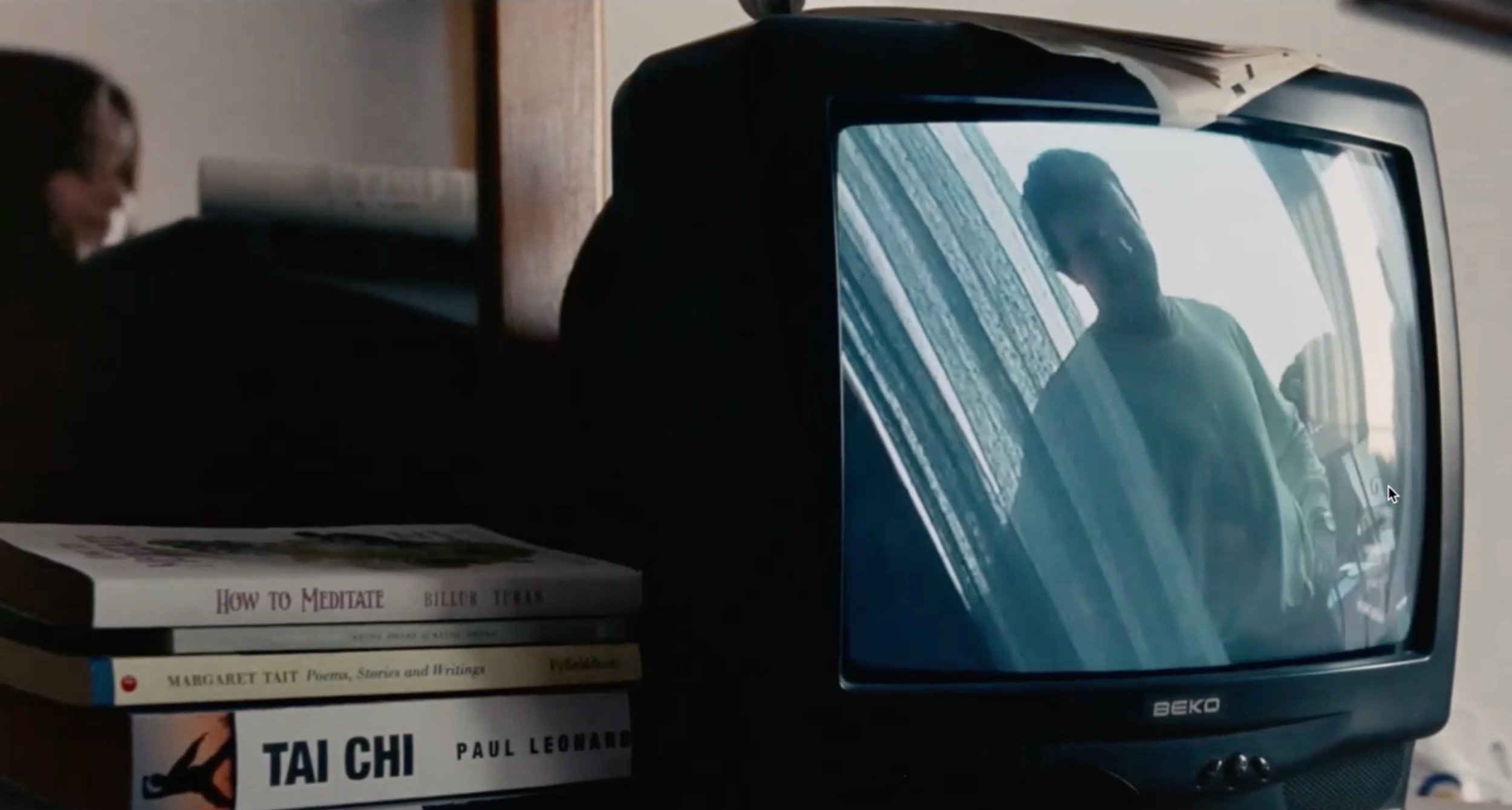

From DISTANT VOICES, STILL LIVES (1988). Writer-Director Terence Davies, Cinematographers William Diver, Patrick Duval.

In my thesis presentation classes at AFI Conservatory a few years ago, with their screenplay close to the shooting script stage, I would have the director describe the “journey of the audience” through each scene of their movie. Its wants, its fears, what it knew, what it didn’t, what it understood, what it deduced, what it suspected, what it anticipated, what their flow of its emotions might be, what questions it was asking — of the story, of the characters, of the world.

Over the course of many years, as this exercise became increasingly refined, these encapsulations grew longer and more granular, invariably becoming longer than the relevant scene itself.

It became, to put no finer point on it, an articulation of a viewer’s stream of consciousness.

Because our minds work so rapidly, many of the responses anticipated were fleeting, subliminal, and perhaps barely afforded conscious realization in the mind of this putative viewer. But the directors intended that their film should give rise to them, not that they had started out with any such purpose, but that they had found it coming about in the course of developing their story and the means of its telling.

To be clear, these chronicles could never, of course, have been definitive. Moments may prompt different responses from the different viewers who make up the audience. Besides, emotions, visceral reactions too, can’t always be put into words — and can be all the more powerful for that. Often, the filmmakers themselves would be uncertain of the response they might be prompting. So, not only were expletives and buzzwords of the day encouraged, but a 'WTF!' was a perfectly legitimate expression of those moments in a movie that for some of us mark our most intense engagement — those instances we cannot define or explain, even to ourselves. The directors accepted this, even encouraged it. If we could nail every nanosecond of our experience in watching a movie, that movie would surely be dead in the water.

Some might nevertheless object that it is not for the director to manipulate the experience of the audience in any way, but that it should be free to engage actively with the movie it watches. The filmmaker as dictator, what’s more, they might justifiably add, robs the viewer of their agency in interpreting the film and taking from it what their individual sensibility and mindset prompts.

That might be true if the director were seeking to render their audience a purely passive entity. When cinema becomes merely consumerist, such can be the case. That was not the purpose of this exercise though. There was no all-knowing imperative demanded of the young filmmakers.

I think it was Syd Field who said the writer should know everything about the character. Abbas Kiarostami, to the contrary, said there should be something “impenetrable” about a character. I go with the Iranian master. Unanswerable questions, ambiguity, irreconcilable opposites, the mystery of the human soul—this is the stuff of story and cinema, not the arid certainty of what can be safely defined and detailed.

But there is, or I believe there should be, a shared experience for an audience watching a movie. The director designs that response, prompting, often indeed manipulating, but never entirely micromanaging the journey the audience makes.

In giving my “Deep Screenplay” course recently, based on my book The Director Meets Their Screenplay, I was reminded by the attendees of the significance of this concept of “The Journey of the Audience.” It wasn’t anything they had come across before. They saw it for what it is — an essential resource for the director in the formulation and making of a movie.

Others might agree:

When I make a movie, I’m the audience. — Martin Scorsese.

The film doesn’t exist without a viewer. And the viewer is most important. — Krźystof Kieslowśki.

Always make the audience suffer as much as possible. — Alfred Hitchcock (my fellow screwed-up Londoner exiled, like myself, in LA.)

Francis Ford Coppola remarked that a film is nothing but shadows on a screen and that the real drama, the real emotion takes place in the hearts and minds of the audience.

When I ask students what they think is a movie’s final destination, they usually reply that it’s the movie theater or the streaming service, as though its existence as an artifact alone suffices. They are wrong. The final place for a film is in the soul of the viewer.

We tend to think of a movie as the capturing of a fiction, of the events of a story. The director stages the action, the actors perform, the camera points at the action, or some part of it, or at something else while events take place offscreen, the results are cut together, and along with sound, a vital partner to image, we have the film.

But there’s another vector…

Wittgenstein asked whether a language spoken by one person and understood by nobody else could really be described as a language. That might prompt the question: could a film seen by no one ever be a film?

The film doesn’t only look inwards into its world, it looks outwards, speaking to its audience. Storytelling isn’t only about story, it’s about the telling of that story too, about its showing, about its revealing, about the fulfillment of these tasks and its intentions in doing so.

Forget “grammar”, forget “coverage”, think, feel, see, and hear as though you were the viewer of your film as you make your film, as you block, lens, light, place and move your camera, as you make the cut or do not make the cut, as you layer your soundscape, your score and source music, as you hone the texture of your image…

You look into the fictional world, and you look out to the viewer as they watch, hear, and experience that world. Your screen is the conduit between the two, the route to the viewer’s heart.

The “journey of the audience” is not some meta concept to be confined to the classroom, I believe that its recognition is central to the act of making a film.

Peter Markham

October 2025