Cinema: Refreshing the Viewer’s Visual Palate

The articulation of the mutable screen

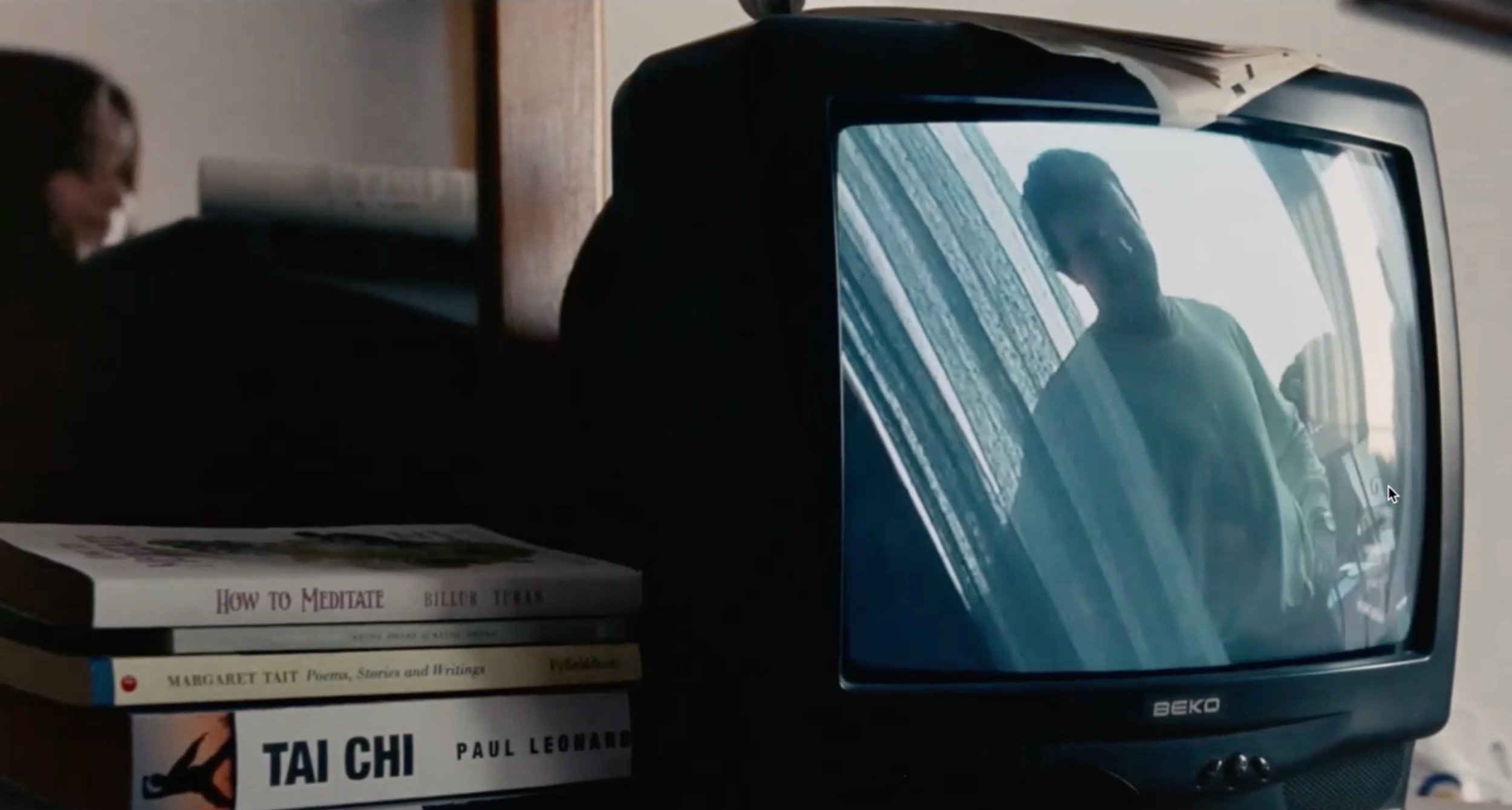

From AFTERSUN 2022, Writer-Director Charlotte Wells, Cinematographer Gregory Oke.

In Walter Murch’s seminal In the Blink of an Eye, he posits six criteria for making the cut, the fourth of which is Eye Trace — the journey of the viewer’s eyes over the screen, from one side to the other, up to down, locked on one spot, transferring to somewhere else…

There is then not only the story a movie tells but also the story of its viewer’s eye trace or eye path, as their attention is drawn to particular places within the frame. Meanwhile, what goes on in other parts can be subliminal, perhaps not taken in at all.

But this is only one example of the constantly changing relationship between the audience and the fluid dynamics of the screen’s canvas.

The movie screen itself, of course, generally remains the same — unless the film employs changing aspect ratios (an effective example of this being Interstellar). Even so, when the filmmaker uses a frame within the frame, the section they define becomes, in effect, its own new aspect ratio. A wide screen is changed to academy ratio, perhaps to something more narrow — maybe to that of a smartphone, as other areas are blocked out by foreground obstructions or taken up by areas of “negative” space.

The director might at times compose several frames within the frame. Windows, doorways, hatches, mirrors, TV screens might contain individual images that contribute to one composite image. Changes of movement or light, the racking of focus, a new emphasis achieved by the orchestration of color or depth, or by shifts of context afforded by dialogue, may switch the viewer’s attention from one segment to another. In these ways, a static frame can be rendered dynamic to the viewer.

A strong instance of this can be seen in Charlotte Wells’ Aftersun, in a scene set in a hotel room. Here, the filmmaker defies the limitations of a restricted location — the room and its adjoining balcony — by using a mirror and a character-operated DV cam that pans, settles, pans wildly again, its images displayed on a TV screen. By adding a pile of books, relevant to one of the two main characters, (one volume is boldly anachronistic and another nicely pertinent to the director’s inspiration), and by using the distorted, faint reflection of action in the room on the TV screen once the DV cam has been switched off, Wells creates a composite frame of interconnected images.

The effect of this is to make the viewer have to work to follow the story. Given that one of the characters relates a recollection from his boyhood, there are other images evoked too — in the viewer’s imagination, on the screen of their mind.

Frames within the frame in AFTERSUN

At one point, Calum, played by Paul Mescal, can be seen in crisp focus in a sliver of space to the extreme left of the frame. With the viewer’s attention firmly fixed on him as he talks, the film’s aspect ratio becomes to the viewer — at least subliminally — narrower than that of a smartphone. Wells thus transforms a peripheral area of the screen into the central one in this moment.

(For all of my formalist preoccupations, let’s not forget the miraculous evocation of emotion in this astonishing debut feature — evidence, should it be needed, of the unity of substance and style in the best work.)

The variability of the canvas the screen offers the viewer does not always require frames within frames of course. Varying shot sizes are in themselves a simple means of visual modulation. From extreme close-ups to breathtaking vistas, from a microscopic cell to entire galaxies, this fluctuating universe of visual language offers the director the choice of the range of shot sizes appropriate to the cinematic idiom of their particular movie.

The oscillation of distance from and proximity to subject matter, meanwhile, adjusts the changing nature of the viewer’s connection to characters and objects. When they see them and when they don’t, how they see them, from the front, from behind, obscured or unobscured, alone or in a populated frame — these permutations also constantly quicken the connection of viewer and screen.

This scale and scope and the contrasts presented apply both to montage and to fluidity within the individual shot. A famous example in the sense of changing shot size, of the contrast between distance and proximity is the crane shot in Hitchcock’s Notorious, in which the camera descends from above a high landing, panning to reveal a wide framing of the party scene in the lobby below, then continues to plunge until the shot focuses on the back of Alicia Huberman, played by Ingrid Bergman, then pushes in further to settle on her closed fist, holding the frame as she opens her hand to reveal the key clutched secretly in her palm.

What this classic shot also reveals is the mutability of the nature of space on the screen. From deep to flat, through mid, variations of space energize the filmmaker’s canvas, concentrating, perhaps restricting, or to the contrary opening up the vision of the viewer — rendered at one moment cavernous, at the next claustrophobic, or vice versa.

Related to this, the axis of the drama and its tension might be lateral, vertical, or deep (x-, y-, z- axes), shifting cut by cut or within a camera move. Characters interact across the frame at one moment, then from foreground to mid- or background at another.

Contrasting compositions also serve to stimulate the viewer’s visual experience — line, shape, proportion are mutable with the filmmaker’s different choices of angle. What might be manifest from the camera placed at eye height, for example, might change radically to a new geometry revealed by one placed overhead.

Movies lacking this cinematic agility, shot for example in endless medium close-ups throughout, interspersed only by wide “establishing” shots, often prove visually dull. Amelie, at least for me, for all its merits posed such an endurance test, its screen increasingly monotonous to behold. (Many loved it, however.) It has to be said though that scenes and sequences in themselves may be intentionally made visually monotonous as the filmmaker traps the viewer in their engagement just as characters in the movie may be trapped in their situation. Same shot sizes, same angles, over and over and there’s no escape — either within the story or for the uncomfortable audience. Effective for a stretch but tough to take and worse, boring, for an entire film.

On the other hand, films with little or no organic visual strategy whatsoever but a random opportunism of form, to me at least, can prove equally alienating.

The viewer’s “visual palate”, as I like to think of it, benefits from refreshment. Like a change or reversal in narrative direction, an oscillation of tone, a shift of place or time, variations in the nature of the screen and the elements within it serve to reinvigorate and maintain the viewer’s commitment.

Peter Markham

March 2025