A Film’s Universe Beyond Character and Action

Photo by Phil on Unsplash

Some filmmakers have itchy fingers. An event finishes/An event begins. ‘Cut to the chase!’ ‘The story must move on!’ We’ve heard it all. The ‘industry professional’ speaks. Something must always be happening. It’s a one-size-fits-all screen in the cult of one individual slogging it out against another individual. ‘Don’t let up!’ ‘Don’t bore!’ the regurgitators stipulate. Right, and ‘Don’t think! Don’t feel!’ ‘Don’t imagine.’ The audience must be rendered passive ‘Don’t stop’, the sure-of-themselves-educator insists, or like the cartoon character who runs of the cliff and keeps running, only to plummet a suspended second later (if anyone remembers them), your movie will nose-dive, your audience’s attention span dropping precipitously with it…

‘The audience is fickle. Grab ‘em by the throat and never let ‘em go,’ said Billie Wilder. Let’s be honest—there was one great filmmaker! Someone we would all do well to listen to. Makes me think of the Safdies and Uncut Gems… Their story on steroids. The violence of the visual. Energy extreme. We’re grabbed—and not only by the throat. We’re taken on what we call ‘a ride’. And there’s no getting out of the speeding, skidding, dizzying vehicle we’re in until it hits its devastating denouement and the movie finishes not with a whimper but a bang.

And yet… is that all there can be?

What happens before the characters arrive and the action starts—or after the action has finished and the characters have left? ‘Nothing’, you may say. But what does that nothing look like? What if we were to see it? The space and setting alone. The colors and tones, the shapes, lines, depth. The light, the dark. The left, the right. The up, the down. Does time pass in this realm devoid of human time? If so, what is the sign of it? Or is it frozen? Static. Stopped like the beat of our hearts as we perceive it?

Show an empty space to someone and they are immediately perceptive. They want to know who or what is about to fill it. (Abbas Kiarostami)

Who is about to appear? Where in the frame will they make their entrance? What is about to happen? And when? We have to look but are made to wait—and so the act of looking is intensified… More than witnessing the screen we experience it.

Or, if the action is over, and if the characters have left the frame, what remains? The echo of it. Of them. The resonance. The ghost of the event. The objects, the room, the hallway, the place, the vista holds a charge, a memory. And just as it lives on in the emptiness before us, so its emotion reverberates within us… and the mystery of it too…

Not the passing gratification of the immediate but the quiet trace of the moment.

Ozu was the master of this compelling absence. His ‘pillow shots’, as Roger Ebert called them, possess the screen as for other filmmakers, and for Ozu himself elsewhere, an actor might, through their performance. The master’s sense of composition and mise-en-scène, of tone and later of color, his elegance of shot design, his aesthetic of grace, of both harmony and contrast (a bright red kettle against the affinity of a room’s muted tones), serves to hypnotize and delight us even as the pain of a story’s drama lingers. We are afforded the privilege of bearing witness as no character in the film can. They’re not there. There’s nobody around, just us. No one to see us. Or it. The emptiness is ours alone. We are free of time, of movement, of being—almost. A little universe we have all to ourselves. And its invisible hint, just maybe, of the numinous…

There’s no there there. But with Ozu, who cares? Each split second of that frame is precious.

The universal principle?—Breath is as much a facet of cinematic narrative as breathless drive. Emptiness offers function also. It punctuates. Its frames build the stanchions of structure, the markers between ‘narrative units’: scenes, sequences, movements, acts. The measure of the dramatic narrative, the perspectives on the world, the ellipses in the passage of time, a weave in the fabric of a film’s visual language. The respite enriches—not a faltering but a replenishment.

The empty frame gives what the page never can—our world without us. What we inhabit discovered uninhabited, like the haunting rendezvous of Antonioni’s L’Eclisse, its lovers failing to turn up as arranged in a place that has no need of them, and had none to begin with. Pure space. Pure time. The pure presence of absence. Plenitude in vacancy. A sense of what might be us from a universe without us.

But the unpopulated image can, in and of itself, yield a dynamic. The tensions of composition with its ikones of visual rhetoric—Bruce Block’s abstract elements of visual language, their arrangement and proportions, and the frames within the frame—and of mise-en-scène—the placement of specific components, characters, and objects within the frame, these serve to animate the inanimate. Energy expressed through a geometry of form and significance that infuses drama into a stillness that exists only without humanity. A combination that takes the eye on a journey over the screen, our ‘eye trace or path’ as we watch a movie, a narrative of the frame that, for its duration, lacks nothing.

The voice of place, of dark and light, of thingness, color, dimension, speaking—as it compels us to listen…

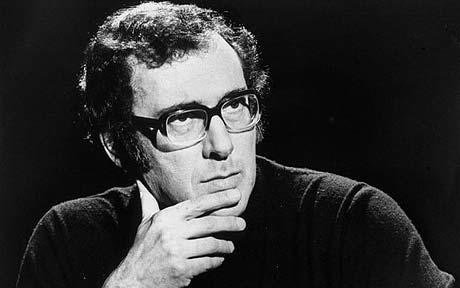

Peter Markham November 2022