I recently saw this post on social media from an aspiring young filmmaker: “Is there any point in studying film history?” Only if you prefer to escape cultural amnesia, I thought, irritated by the very idea of not studying the work of filmmakers over the decades. But then, annoyed by my own annoyance, I reflected that this person had every right to ask such a question. Not only that but the fundamental nature of the enquiry is to their credit. They weren’t saying there was no point, just asking whether there was one and if so what it might be. While I have always taken it for granted that there is indeed a point, it would never have occurred to me to think it through had that prospective cineaste not asked his question. The term “film history” could mean many things of course: the history of film production and manufacture, of filmmaking technology, of distribution, of movie stars and celebrities, of the culture and community of filmmakers and film lovers. While I wouldn't for a moment denigrate the historians of any of those topics, nor seek to limit the boundaries of film history, or any history, I would have to admit it’s the language of the moving image and the storytelling it facilitates, and how generation after generation find ways of making this work, that for me is always the most exciting arena.

A Canterbury Tale, written by Emeric Pressburger, directed by Michael Powell—the duo calling themselves The Archers, who were responsible for several of the greatest British movies ever made—was released in 1944. The film begins with a group of medieval pilgrims journeying across the English countryside to Canterbury Cathedral, inspired in the Powell-Pressburger mind by the pilgrims of Chaucer’s 14th century Canterbury Tales. One of the pilgrims releases a falcon into the sky. As the pilgrim peers up, the bird soars away into the heavens. Then, as it sails through the air, we see something unexpected happen. There's a transition in image, in time, sudden, magical, inspired. With no cut, no camera move, without reframing or adjustment, the falcon transforms into a Spitfire, the single-engined fighter plane adept at combating the Nazi Luftwaffe as it attacked Britain (and once, in the process, taking out my family’s home—empty at the time, as luck would have it). The sky of the 1400s becomes the sky of World War II. Pressburger and Powell have defied the constraints of time and culture. The poetry of the image, of the juxtaposition of images has been rendered a narrative device. Creature has morphed into machine, nature-made into man-made. The past has become the present, or what was for the filmmakers the present. Chaucer’s literature has become cinema and the story of the film moves on. Simple, clear, innovative, masterly. One example of the combined genius of Powell-Pressburger.

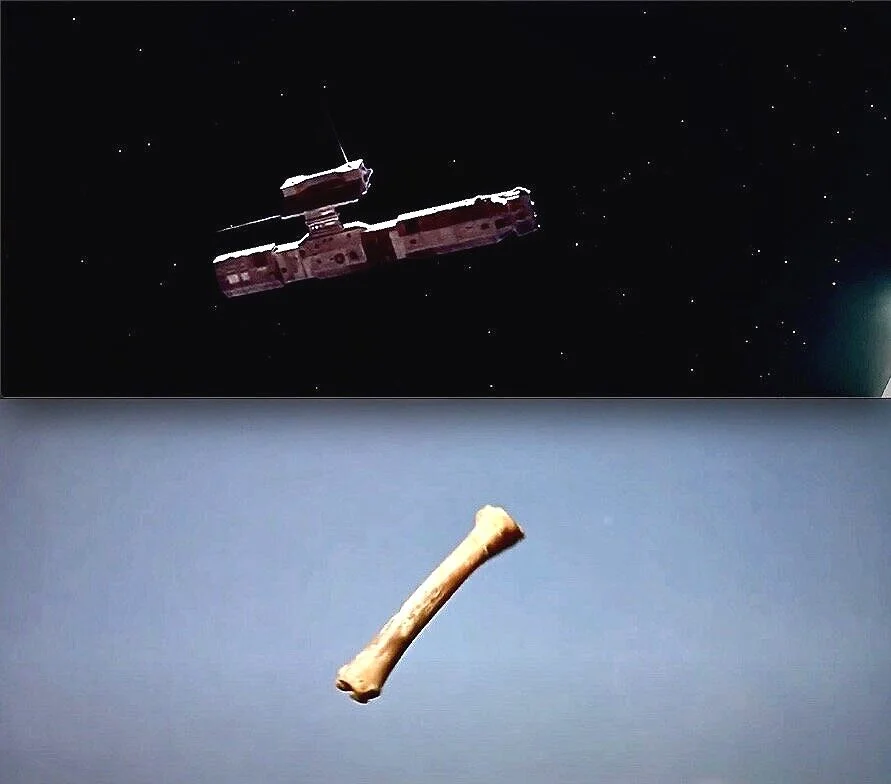

It was Martin Scorsese who pointed out to me that Stanley Kubrick's similarly deft transition in 2001—a fibula tossed into the air by a triumphant hominin transformed mid-spin into a tumbling spacecraft—was inspired by that very gem of cinematic language in A Canterbury Tale. The past, through Kubrick's agency, becomes the future. With a single cut, Powell-Pressburger travel through 500 years while with his edit, Kubrick spans not just countless millennia but human evolution over millions of years. Primitive weaponry is rendered state of the art technology, brow ridges frontal lobes, savagery grace, sky cosmos. And that's only the film’s beginning… what’s to follow in every way meets the lofty expectations set up by its prelude. The mystery only deepens, the journey taken only expands, the film only becomes more magnificent…

What would 2001 have been, had Stanley Kubrick not seen that earlier movie? Would he have found some other manner of visual time travel? A different juxtaposition of imagery? But what might that have been? And what, come to think of it, had been the source of inspiration for Emeric Pressburger and Michael Powell to begin with? Had they seen an earlier film that made use of some similar transmutation, its combination of affinity and contrast affording a comparable thrill of dissonance? Or had they simply looked up one morning as a bird flew overhead before yielding the empyrean to some subsequent Supermarine Spitfire? Was it movie or was it life that provided them with the solution to the challenge of girding the centuries?

Jean-Luc Godard opined that there are two kinds of director: those of “free cinema” who walk in the street with their head up, and those of rigorous cinema who walk with their head down… fixing their attention on the precise point that interests them. Powell-Pressburger, it strikes me, were of the latter category, as was Kubrick. Those of this rigorous tribe, perhaps, are the ones who derive most benefit from the riches of past cinema, from its reservoir of storytelling language. For them, that language, the nature of the image, its selection, its framing are indivisible from the thing itself. There is none of the assumed duality between content and style—the baggage of pre-20th century preconceptions of a fixed objective reality. The world and story of the film, the screen on which it plays out, and the emotion, thought, and gut sensation of the audience work together as one symbiosis, the process that is the movie. In truth though, there never was a tabula rasa upon which the “free” cinema filmmakers might conjure their images, drawn from life to be merely transplanted onto the blank screen. What is witnessed in the world must inevitably be filtered through the acculturation of the screenwriter, the director, and the cinematographer before being transferred to their movie. Has there ever been a director who has never seen a film? A single film? Could there ever be? How could anyone make a film without knowing what a film is? (Louis Le Prince was perhaps an exception, when he shot the modest seconds of the Roundhay Garden Scene in 1888, or maybe Thomas Edison was a virgin filmmaker when he began to make shorts five years later, but even they, and the contemporary Lumiere brothers, and other pioneers, had to be aware of still photography, as photographers had previously been informed by the work painters.) And would that film or those films seen before not have remained to some extent or other in the filmmaker’s mind as they visualized their own? Wherever it is that art begins, it does not begin in a vacuum. Whether we acknowledge it or not, we copy, we steal, we develop, we subvert, we reinvent, we plunder and reuse whether consciously or unconsciously, what has come before us. No way around it, not without going back to those Kubrickian hominids and their oblivious frolics.

A directing fellow at AFI, outstandingly talented and subsequently enormously successful, once remarked to me after we’d spent hours in class going scene by scene, shot by shot, cut by cut through a Hitchcock movie, that “we don't make films like that anymore”. Why, he asked, should we have spent all this time analyzing the visual storytelling of a movie made so many decades ago? He was, I suppose, asking the self same question as the aspiring filmmaker in that post. My reply was that the class was not only about the solutions Hitchcock found to the challenges he faced, but also—and perhaps primarily—about those challenges and questions themselves, universal to movie storytelling throughout the decades. I wasn't telling him to make movies exactly like Hitchcock’s, I said—although that would perhaps be no bad thing—but to be able himself to find the key questions, ones that otherwise he might not spot, so that he might come up with his own solutions, his own modes of visual storytelling. I might have added that language—any language, on the page, on the screen, of the spoken word—is constantly shifting and changing as it’s pushed and pulled by the pressures of culture, the search for meaning, for function, for the need for renewal, so that it can be ever fresh and vibrant. The study of even a contemporary movie might, given his preconceptions of ephemerality, be rendered past its sell by date. Good movies—and how we define the term “good” is of course a matter of debate—do not have a sell by date, nor, even, do many “bad” movies, from which we can also learn so much.

We know better than our predecessors, the common assumption goes. We are more sophisticated, more hip, less constrained by tradition, more badass than the old-fashioned dead. We have digital cinematography. We have Avid. We have smart phones. We edit on laptops. Sure. So what happens next? Future generations will top us, as each in turn, one by one, tops the other, a progression of the exceptionalism of the present defiant in the face of the wisdom not only of the ancients but of those still warm in the grave. Technologies change, yes, sensibilities shift, cultures evolve, and we find different ways of telling stories. But many of those ways will be echoes and variations of past approaches whether we are aware of it or not. Our need for story, to hear, to read, to watch, to experience will not however alter—it’s through story and storytelling, the catalyst for our emotional and cognitive engagement with existence, that we come to understand who we might be and grasp some sense of the mysterious universe in which we find ourselves.

Such a mysterious firmament presides over 2001, itself now an “old movie”. Is there any point in studying it? Is there any point in studying If, Rosemary’s Baby, Once Upon a Time in the West—films made in the same year? What’s to learn from Lindsay Anderson, Polansky, Leone? Only the dramaturgy of cinema, the language of the screen, the intractable and paradoxical truths of myth and life. Only the troubling but sublime glory of the image. Only the art of what will happen next? Only the emotions and sensations inside us all. Only the world in which we find ourselves. Only us.

And it’s that that is the point, the point of studying film history.

Peter Markham November 2020

Author: What’s the Story? The Director Meets Their Screenplay. (Focal Press/Routledge)

https://linktr.ee/filmdirectingclass